STED and AFM

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy

Members:

Thomas Schmitt

The introduction of fluorescent dyes, particularly fluorescently labeled antibodies, proteins, and other probes capable of specifically binding to target molecules, represented a major advancement in microscopy by enabling the determination of their subcellular localization using a fluorescence microscope (Figure 1a). These tools enabled precise visualization of virtually any protein of interest, facilitating detailed studies of cellular structures, protein localization, and dynamic processes such as translocation. However, conventional fluorescence microscopy collects light from the entire depth of the specimen, resulting in limited Z-axial resolution and frequent artifacts from out-of-focus structures. While this issue could be partially mitigated by using thin tissue sections or cell monolayers, it is not fully resolved by these methods.

To overcome this limitation, confocal microscopy was developed. This technique uses a spatial pinhole to selectively detect light from the focal plane, effectively eliminating out-of-focus light and allowing for optical sectioning (Figure 1b). As a result, confocal microscopy produces sharper images and enables the reconstruction of high-resolution three-dimensional representations even of thicker samples. Nonetheless, despite its improved resolution, confocal microscopy remains fundamentally limited by the wavelength of laser light, restricting its resolution to approximately 200 nm. This barrier prevents the visualization of many subcellular structures with finer detail.

To address this limitation, various super-resolution microscopy techniques have been developed. Among them, Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) microscopy, used in our laboratory, has proven particularly effective. STED employs a dual-laser system: the first laser excites fluorophores within the sample, while the second, higher-energy laser is refracted into a ring and depletes fluorescence around the center region by reversible bleaching. Only fluorophores at the very center remain active and detectable, resulting in a significant increase in spatial resolution. Moreover, STED provides more uniform illumination patterns across different wavelengths, further enhancing image quality and consistency (Figure 1c).

Figure 1: Schematic of fluorescence microscopy techniques a) basic fluorescence microscopy. b) confocal microscopy (modified from: University of Queensland). c) Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy (modified from: Welt der Physik)

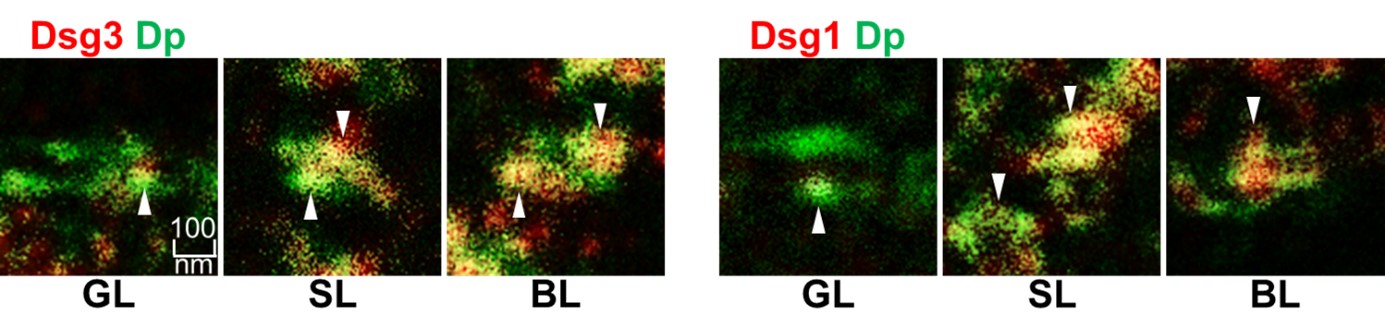

Using STED microscopy, we successfully resolved the ultrastructure of desmosomes, key intercellular junctions responsible for cell–cell adhesion in epithelial tissues. This super-resolution technique enabled us to demonstrate that the composition of desmosomes, particularly with respect to their adhesive cadherin components desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) and desmoglein 3 (Dsg3), varies across different layers of the epidermis. Distinct membrane domains enriched in either Dsg isoform became discernible (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Representative images of single desmosomes as found in the most superficial Granular Layer (GL) Spinous Layer (SL) and Basal Layer (BL) stained for Desmoplakin Dp in green and Dsg1 or Dsg3 in red (White arrowheads indicate domains enriched or depleted in the Dsgs) (From Schmitt et. al Frontiers in Immunology 2022).

Furthermore, STED allowed detailed visualization of the keratin filament network and facilitated quantification of keratin filament insertion into desmosomes. We observed significant retraction of keratin filaments from the plasma membrane in response to treatment with Pemphigus vulgaris autoantibodies (PV-IgG), which are known to impair desmosomal adhesion by targeting desmoglein adhesion (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Representative images of normal human epidermal keratinocytes treated with pemphigus autoantibodies (PV-IgG) or antibodies from healthy volunteers (cIgG) stained for Keratin in green and Dsg3 in red (White arrowheads indicating depletion of Dsgs and yellow compared to white spans indicating the retraction of keratins from the cell border towards the nucleus) (From Egu and Schmitt et. al J Invest Dermatol 2024).

Using STED microscopy, we could achieve an adequate resolution to visualize desmosomes in detail (Figure 4 a). This allowed both qualitative and quantitative evaluation of alterations in the desmosome ultrastructure, including alterations in desmosome size, Dp-plaque thickness, Dp-Plaque distance, desmosome splitting, internalization of desmosomes, linear streaks (indicating desmosome remodeling) and clustering of Dp in certain regions induced either by PV-IgG (Figure 4 b) or Anisomycin (Aniso) (Figure 4 c), an activator of p38MAPK (a signaling kinase central for PV-IgG induced effects) (Figure 4). These features were previously only accessible via electron microscopy, which made it impossible to correlate the structural changes with individual proteins. Our findings using STED microscopy show very comparable results for these features. However, STED additionally allows to distinguish the roles of individual desmosomal components and even correlate them to factors like translocation of signaling proteins to the desmosomes.

Figure 4: Qualitative summary of effects of PV-IgG or Anisomycin (Aniso) treatment on the Dp plaque ultrastructure. Representative STED-microscopy images (Scale bars left to right 2 µm, 500 nm, 100 nm or yellow: 250 nm). a) Control condition. b) effects of PV-IgG treatment. c) Effects of Aniso treatment. The lines indicate measurements of the example desmosome under control conditions. Red: length and width, purple: Plaque thickness, blue: Plaque distance. Green arrows indicate missing halfs of split desmosomes, red arrows indicate linear streaks, blue arrows indicate areas where Dp staining is clustered and red circles indicate double Dp structures in the cytoplasm below the cell border. Green boxes indicate zoomed areas (From Schmitt et. al Frontiers in Immunology 2025).

These examples should highlight the apparent advantages of STED microscopy for the investigation of ultrastructural alterations of subcellular structures like desmosomes or cytoskeletal filaments.

Recent Publications

T. Schmitt, J. Huber, J. Pircher, E. Schmidt, J. Waschke. The impact of signaling pathways on the desmosome ultrastructure, Frontiers in Immunology, Jan 15, 2025 Volume 15 – 2024. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1497241

D. T. Egu*, T. Schmitt*, N. Ernst, R. J. Ludwig, M. Fuchs, M. Hiermaier, S. Moztarzadeh, C. S. Morỏn, E. Schmidt, V. Beyersdorfer, V. Spindler, L. S. Steinert, F. Vielmuth, A. M. Sigmund, J. Waschke, EGFR Inhibition by Erlotinib Rescues Desmosome Ultrastructure and Keratin Anchorage and Protects Against Pemphigus Vulgaris IgG-Induced Acantholysis in Human Epidermis, J Invest Dermatol 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.jid.2024.03.040

*shared first authorship

T. Schmitt, C. Hudemann, S. Moztarzadeh, M. Hertl,R. Tikkanen, J. Waschke. Dsg3 epitope-specific signalling in pemphigus, Frontiers in Immunology, Apr 18, 2023. 14:1163066. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1163066

T. Schmitt, J. Pircher, L. Steinert, K. Meier, K. Ghoreschi, F. Vielmuth, D. Kugelmann, J. Waschke: Dsg1 and Dsg3 Composition of Desmosomes Across Human Epidermis and Alterations in Pemphigus Vulgaris Patient Skin, Frontiers in immunology, 25 May 2022; Vol. 13, 884241. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.884241

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy combined with atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Members:

Michael Fuchs

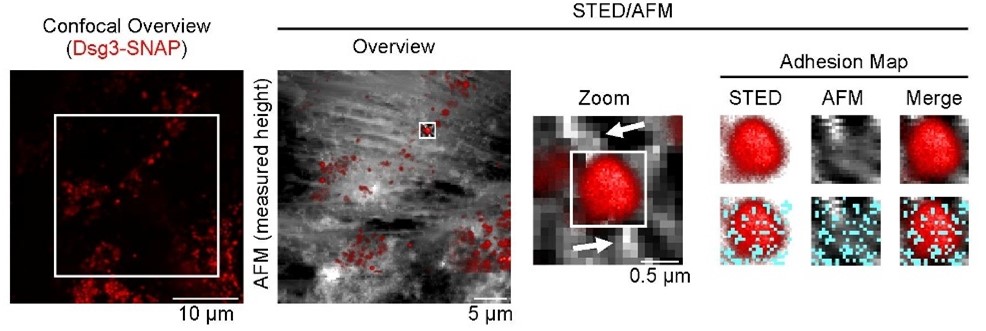

STED microscopy in combination with AFM enables simultaneous super-resolution imaging and mechanical characterization at the single molecule level. This hybrid technique allows precise localization of proteins while also measuring their mechanical properties, providing valuable insights into cellular adhesion mechanisms. AFM topographic imaging and STED can be aligned within the hybrid setup.

Figure 1: Schematic of a STED/AFM setup and exemplary STED/AFM measurement on murine keratinocytes with labeled actin cytoskeleton. From Fuchs et al., CMLS, 2023.

By functionalizing the AFM tip with specific proteins, such as recombinant desmoglein 3 (Dsg3), it is possible to perform single-molecule force spectroscopy between the tip-bound protein and its binding partner on the cellular surface. This approach allows for the measurement of various biophysical properties of desmosomal cadherin interactions, including unbinding forces, interaction lifetimes and the quality of cytoskeletal anchorage. The transfection of fluorescently labeled Dsg3 molecules enables the identification of single Dsg3 clusters. In combination with cytoskeletal filament structures, individual desmosomal structures can be identified and visualized, allowing targeted force spectroscopy measurements at single desmosomes.

Figure 2: STED/AFM measurements on human keratinocytes transiently transfected Dsg3 (red). High-resolution imaging reveals Dsg3 clusters (STED, red) located between incoming elevated cytoskeletal filament structures (AFM), indicating desmosomes. High-resolution adhesion mapping shows specific interactions (cyan dots) between the AFM functionalized tip (Dsg3-Fc) and the desmosomal Dsg3 cluster. From Fuchs et al., BJD, 2025.

The STED/AFM approach offers a powerful platform for correlating molecular localization with mechanical function, advancing our understanding of cellular adhesion processes. Using this hybrid technique, we aim to investigate the mechanisms of desmosomal adhesion. Furthermore, this technique is a promising tool for elucidating the molecular mechanisms of various pathologies, such as the autoimmune blistering disease Pemphigus vulgaris (PV). The technique can also be used to obtain information about the mechanical properties of cells. By measuring parameters such as the Young´s modulus, we can identify rigid cellular regions and correlate them with cellular proteins, such as cytoskeletal components, visualized simultaneously using the STED microscopy. By applying this method, we seek to understand the pathomechanism of such diseases at the single-molecule level.

Recent publications

Fuchs M, Möchel M, Radeva MY, Schmitt T, Yazdi AS, Hashimoto T, Waschke J (2025)

In desmosomes direct inhibition precedes p38MAPK-mediated uncoupling to reduce Dsg3 adhesion by pemphigus autoantibodies. Br J Dermatol.:ljaf142. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljaf142. PMID: 40264374

Fuchs M, Radeva MY, Spindler V, Vielmuth F, Kugelmann D, Waschke J (2023)

Cytoskeletal anchorage of different Dsg3 pools revealed by combination of hybrid STED/SMFS- AFM. Cell Mol Life Sci. 80(1):25. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04681-9. PMID: 36602635 Free PMC article.

Steinert L, Fuchs M, Sigmund AM, Didona D, Hudemann C, Möbs C, Hertl M, Hashimoto T, Waschke J, Vielmuth F (2024).

Desmosomal hyper-adhesion affects direct inhibition of desmoglein interactions in pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 144(12):2682-2694.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2024.03.042.

Egu DT, Schmitt T, Ernst N, Ludwig RJ, Fuchs M, Hiermaier M, Moztarzadeh S, Morỏn CS, Schmidt E, Beyersdorfer V, Spindler V, Steinert LS, Vielmuth F, Sigmund AM, Waschke J (2024)

EGFR Inhibition by Erlotinib Rescues Desmosome Ultrastructure and Keratin Anchorage and Protects Against Pemphigus Vulgaris IgG-Induced Acantholysis in Human Epidermis.

J Invest Dermatol. 44(11):2440-2452. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2024.03.040 PMID: 38642796 Free article.

Sigmund AM, Winkler M, Engelmayer S, Kugelmann D, Egu DT, Steinert LS, Fuchs M, Hiermaier M, Radeva MY, Bayerbach FC, Butz E, Kotschi S, Hudemann C, Hertl M, Yeruva S, Schmidt E, Yazdi AS, Ghoreschi K, Vielmuth F, Waschke J (2023)

Apremilast prevents blistering in human epidermis and stabilizes keratinocyte adhesion in pemphigus. Nat Comm, 14(1):665. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36464-6. PMID: 36750581 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

Fuchs M, Foresti M, Radeva MY, Kugelmann D, Keil R, Hatzfeld M, Spindler V, Waschke J, Vielmuth F. (2019)

Plakophilin 1 but not plakophilin 3 regulates desmoglein clustering. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019 Sep;76(17):3465-3476. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03083-8. Epub 2019 Apr 4. PMID: 30949721; PMCID: PMC11105395.